Nearly every gardener has purchased a plant that was propagated through grafting. Grafting has been used by plant growers for thousands of years, and many of the most popular shrubs and trees sold at nurseries have been grafted. However, grafting typically involves a more complex process than growing a plant by seed, so why bother? The answer is fairly simple: Sometimes grafting is the only viable method of plant propagation.

The extra effort is worth it

Unlike seed production, grafting is a form of asexual plant propagation. As a result, a plant propagated by grafting, which uses a piece of the parent plant called a scion, results in a genetic clone of the parent plant. This is incredibly important, because it allows plant growers to predict the performance and characteristics of the grafted plant. A sugar maple (Acer saccharum and cvs., Zones 3–8) that’s been grown from seed may have a wide range of forms and fall foliage colors across the population of seedlings, in a similar way to how human siblings all look slightly different. But a grafted cultivar of sugar maple should have a form, fall foliage color, and growing requirements based on those of its parent, like two identical twins. A thousand of these plants should look and perform the same given the same growing conditions.

You can also asexually reproduce plants using rooted cuttings to get a perfect clone, but many plants are very difficult to root as cuttings, and the low success rate of this method prevents it from being economically viable. The cuttings that do survive may also have inferior root systems to those of their parent plant. By contrast, grafting has a high success rate, making it the best bet for asexual reproduction in order to produce a clone. Grafting is also used to improve the performance and aesthetics of plants. Specific understocks are paired with specific scions to produce plants with better disease or pest resistance, more durable stems and roots, and better growing habits, among other desirable traits.

Although most people associate grafting with trees and shrubs, it’s not just woody plants that are grafted. Herbaceous plants such as tomatoes and succulents are commonly grafted as well. While you may be able to graft a certain plant using several different methods, some species and varieties grow better with certain methods over others. A grafter’s skill and efficiency also determines which methods are best to use.

Common Grafting Terminology

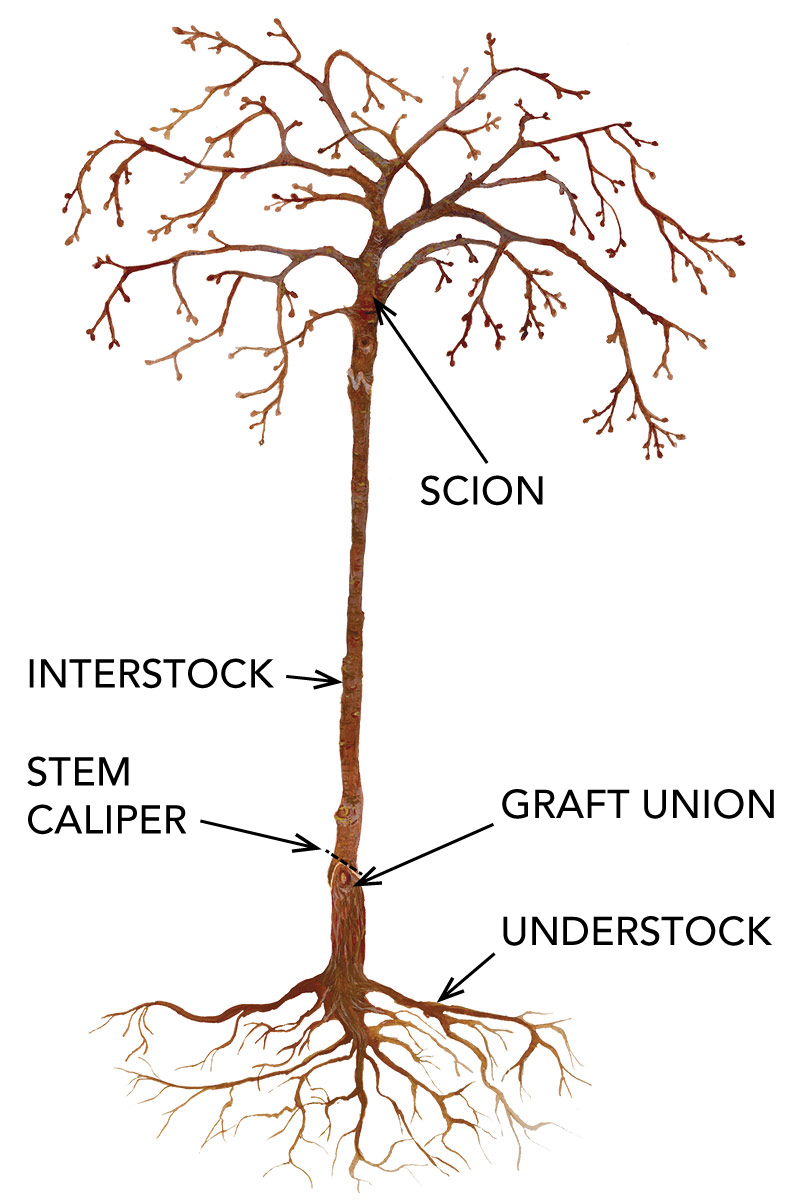

To understand grafting, it’s necessary to learn some of the terms used to describe it.

Scion:

This is a section of plant tissue, such as a single bud or a branch, originating from the desired mother plant and surgically inserted into the understock.

Understock

The understock is the plant material that will provide the root system for the scion to be grafted onto. During the entire life of the grafted plant, the roots of the understock will support the grafted plant that will grow from the scion, but the understock will retain its genetic material. (You may also hear understock referred to as “rootstock.”)

Interstock

In some two-stage grafting techniques, a root system is used from one plant, an interstem is used from another plant (often to create a stout trunk), and the final scion is grafted to the top to create the desired variety.

Stem caliper

This refers to the distance across the center of a grafting cut.

Graft union

This is the actual incision point of the graft—the spot at which the scion, interstock, and/or understock connect.

The science behind grafting

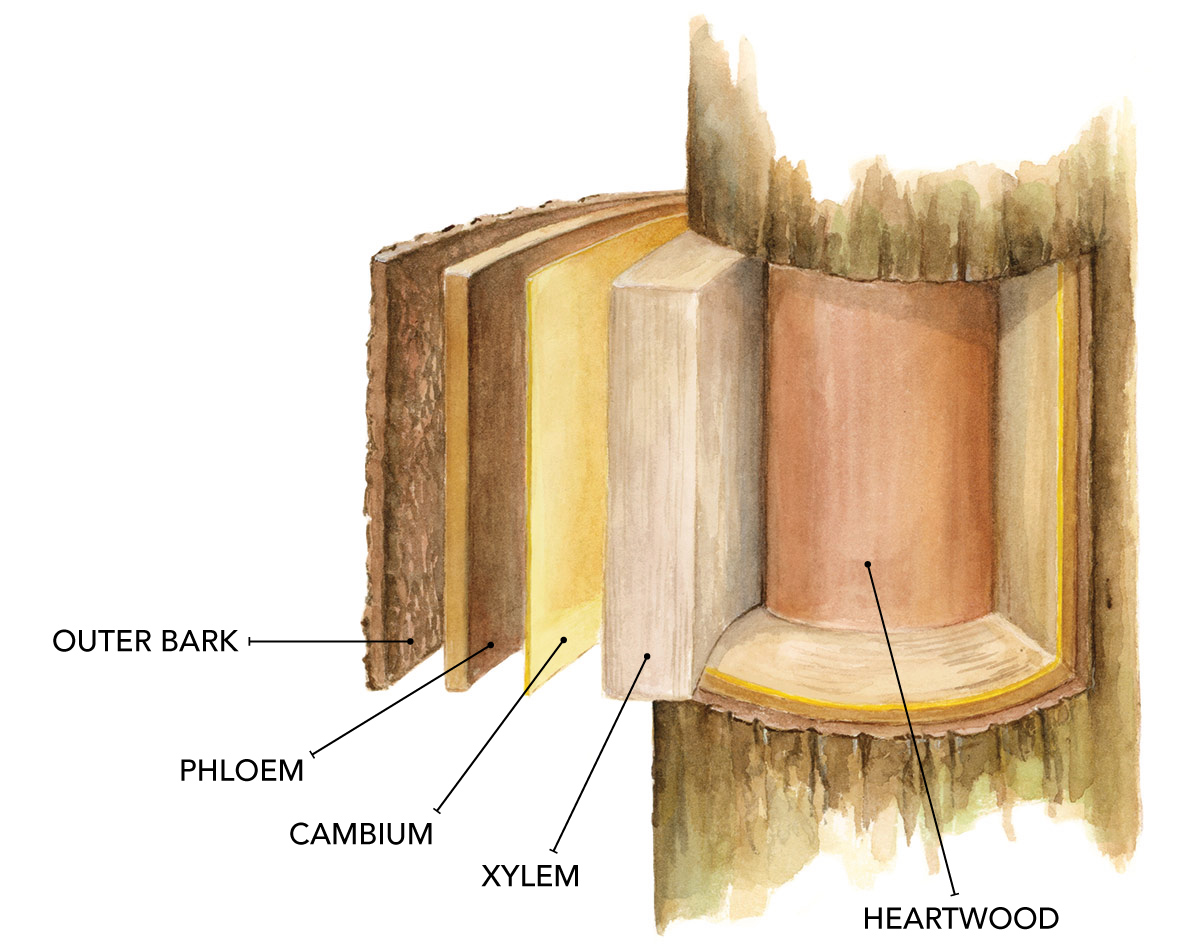

An incredible little layer of actively growing cells lies underneath the bark or epidermis of plants. This layer of cells, called the cambium, multiplies rapidly and grows laterally, producing old cells that are pushed in two directions. The cambium cells that grow toward the inside of the stem become xylem cells. The xylem tissue is made up of tubelike cells that carry water, nutrients, and hormones from the roots to the foliage. As these cells age, die, and are replaced, they become the dead wood at the center of the tree, called the heartwood. The cambium cells that grow toward the outside of the stem are called phloem. These cells transport carbohydrate-rich sap and hormones from the foliage to the roots. With age, phloem cells become the bark or outer layer of plants, and they slough off with stem expansion. A tree only expands in girth by growth of the cambium; height is achieved through a different process.

When you make a smooth, straight incision into the stem of a scion or an understock, you expose a cross section in which these cambium-tissue layers are clearly visible. The simple objective of grafting is to make incisions that allow you to match up the cambium layers of the understock and the scion so that they are aligned, in close contact, and with minimal airspace or imperfect fits. The graft union then needs to be secured by tying the scion and understock together to maintain the alignment. The cambium layers will then heal into a graft union. Once healed, the highway of phloem and xylem cells can resume their job of transporting water, nutrients, hormones, and other materials from the understock to the scion as the plant resumes normal growth.

You might be wondering how far grafting can go. Can you graft a peach tree onto an apple tree, for instance? The answer is no. Much like how a blood transfusion requires a matching or universal blood type, for grafting to be successful, understocks and corresponding scions need to be closely related. How closely depends on the plants you are trying to graft. Typically, species within the same genus are grafted. However, there are exceptions. It’s possible to graft certain varieties of false cypress (Chamaecyparis spp. and cvs., Zones 3–9) onto an arborvitae (Thuja spp. and cvs., Zones 2–9) or a juniper (Juniperus spp. and cvs., Zones 2–10), for example. (These three genera are in the same family, Cupressaceae.) If the scion and understock are not related closely enough, the result will be incompatibility in the graft union. Incompatibility means that nutrients, water, and hormones are not transmitting well from the understock to the scion, leading to the eventual death of the plant.

How plants grow determines how grafting works

The cambium layer is the actively growing part of a plant. Old cambium cells become the xylem and the phloem. Dead xylem tissue in turn becomes the heartwood, while dead phloem tissue becomes the bark (or outer layer). In order for grafting to be successful, the cambium layers of the scion and the understock must connect.

Create the conditions for the graft to take

As when tackling any project, you must first gather the proper tools. Grafting requires a very sharp knife. You will also need materials to secure the graft. There are products made for this called grafting strips and grafting tape (also referred to as budding strips or budding tape). You can also use masking tape or electrical tape, but those materials are difficult to remove. An older method is to use grafting wax painted onto the graft union to seal the area; however, this is messy and very time-consuming.

After gathering the right tools, you will need to make sure you are grafting at the right time. Most grafting of woody plants is done during winter. (Grafting of herbaceous plants can be done at any time.) By grafting in winter when the scion plants are dormant, you reduce stress. This reduces the likelihood of desiccation of the graft. Most understocks perform best when the root systems are warmed for a period of a few weeks to initiate root growth. This is usually done by allowing the plants to go dormant naturally and then bringing them into an environment with a heated concrete floor and cool air temperature. This also allows grafters to do a liquid feed on the dormant plants to bank some nutrients for use during the healing of the graft union. Once the root system shows some white root tips, most species are ready to be grafted.

Scion wood is usually gathered directly from mother plants or purchased from nursery suppliers. Scions can be stored in a high-humidity cooler. Most varieties prefer to be grafted within a week or two of cutting from the mother plant. It is possible to graft woody plants during the summer, but the scion leaves are usually removed to reduce stress, leaving only a small stub on the end of the leaf stems (petioles). They are then moved into a greenhouse with lots of shade, creating an environment with reduced temperatures but high humidity.

After a graft, plants need to recuperate in order for the graft to heal and be successful. They need to be in a greenhouse or a similar environment with moderate temperatures, high humidity, good ventilation, and sufficient but not excessive light. This allows the plants to begin growth without any additional stress. These conditions help to prevent scion desiccation during the 10 to 14 days it takes for the cambium to begin to heal and bridge the graft union. Healthy growth from the scion means the graft union has taken.

Success in grafting plants involves a combination of good preparation, consistent procedures, and postgraft care. Any failure in these areas will sabotage the process. Most gardeners can appreciate the sheer joy of watching healthy plants grow. The same is true for grafters who use their skills to help overcome the hurdles that Mother Nature can throw their way. After all, grafting is the only way that some of our favorite plants exist.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Two Grafting Techniques

Cleft and side veneer are two frequently used grafting methods in horticulture. Each has its pros and cons.

3 Less-Common Grafting Methods

Here are three more types of grafting, how to do them, and what situations you can use them for.

Brian Decker is a horticulturalist and owner of Decker’s Nursery in Groveport, Ohio, a wholesale nursery that specializes in plant propagation and grafting.

Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in