Invasive plants are more than just weeds. Beyond the garden they can cause serious economic and environmental damage, and sometimes even harm to human health. Invasive nonnative species typically tolerate a wide range of conditions and easily outcompete other plants through prolific seed dispersal and rapid growth rates. These successful adaptations are compounded by a lack of equalizing agents, such as pests and diseases, that would typically be present in the plants’ native ranges.

Identifying and removing problematic plant populations will make your backyard more wildlife-friendly and may even prevent the horticultural invaders from degrading nearby wild areas.

With some good research and well-timed interventions, you can confidently remove almost any invasive plant from your garden. What a great way to make more room for the beautiful, wildlife-friendly plants that you love!

1. Identification is an essential first step

Invasive plants vary from region to region, so it is important to find out which species are problematic in your area and to identify the ones that are growing in your garden. A good place to start is with an internet search or a conversation with your local extension agent. Plant identification apps such as Seek by iNaturalist are useful tools; however, they sometimes misidentify plants, especially those that look similar to native species. The Invasive Plant Atlas of the United States (invasiveplantatlas.org) is a great place to find species information, images, distribution maps, and early-detection reporting procedures. Plant identification groups on social media are another helpful resource, and you may even be able to find a group that is specific to your region.

Once you are familiar with what you are looking for, it is important to be vigilant in monitoring your property. Early intervention can save you work in the long run, since a small population is a lot easier to control than large one.

2. Stop seedy spreaders before they mature

Seed tends to be the most common way that unwanted plants enter a property. The most egregious seed producers are often annuals and biennials like stiltgrass and garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Even just a few plants can produce copious amounts of seed and quickly colonize open spaces, so preventing seed production is the key to getting control. This can be as simple as mowing, string-trimming, or deadheading the plants before their seeds mature.

Because of the sheer volume of seeds that annuals and biennials produce, a seed bank can quickly develop in the soil. When this happens, it can take a few years of management to get the situation under control. Adding an appropriate layer of mulch to open areas will greatly reduce the number of dormant seeds in the soil that can germinate.

Aggressively seeding perennial species, such as purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus), present an additional challenge. Not only do they need to be managed for seed production, but the plants must be removed as well. This can be done manually by digging the offending plants out and disposing of them. Herbicides should only be used as a last resort, when mechanical removal is not a viable option.

Where did they come from?

Many invasive species were intentionally introduced as ornamental landscape plants, and their invasive potential was only recognized many years later. This is the case for Callery pear (Pyrus calleryana) and Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii). Kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata), sometimes called “the plant that ate the South,” was once widely promoted for erosion control. Other species arrived as stowaways in shipments from overseas. For example, stiltgrass (Microstegium vimineum) is believed to have entered the country as packing material.

|

|

|

|

|

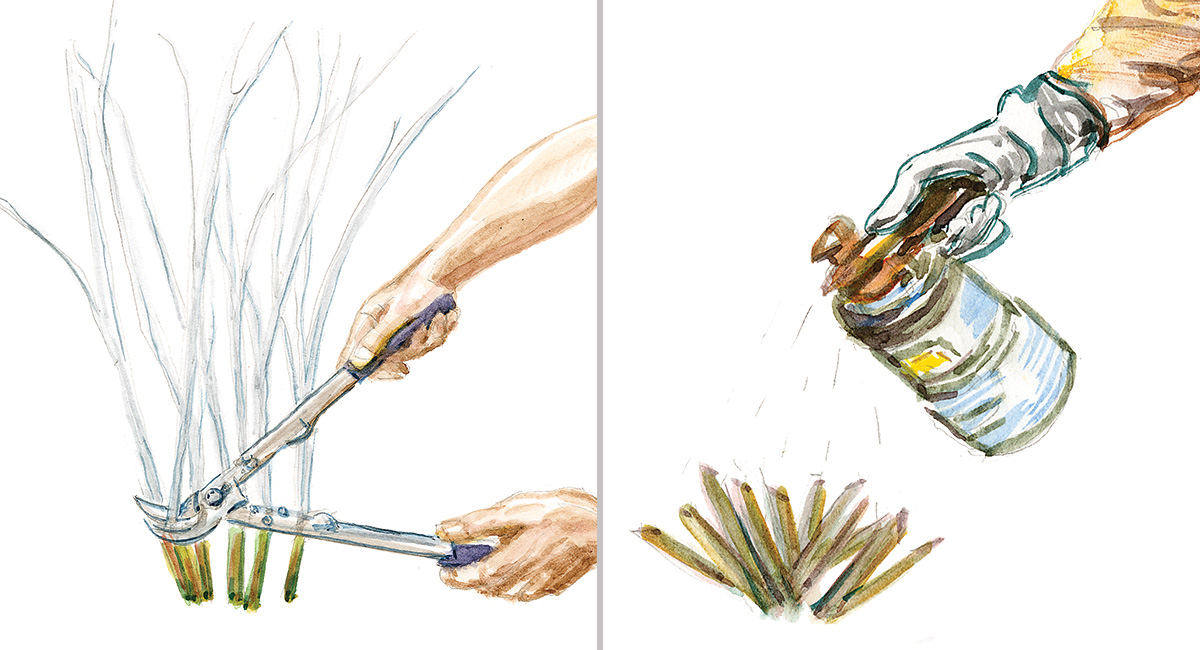

3. Stay on top of underground invaders

This group of plants can spread by underground plant parts—for example, the rhizomes of Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica), the stolons of English ivy (Hedera helix), or even small tubers, like those of lesser celandine (Ficaria verna). For these plants, the best defense is a good offense. If you can identify and remove them while they are small, the process will be relatively easy. Once established, they become more difficult to manage because they reproduce vegetatively, even from small plant parts left in the ground.

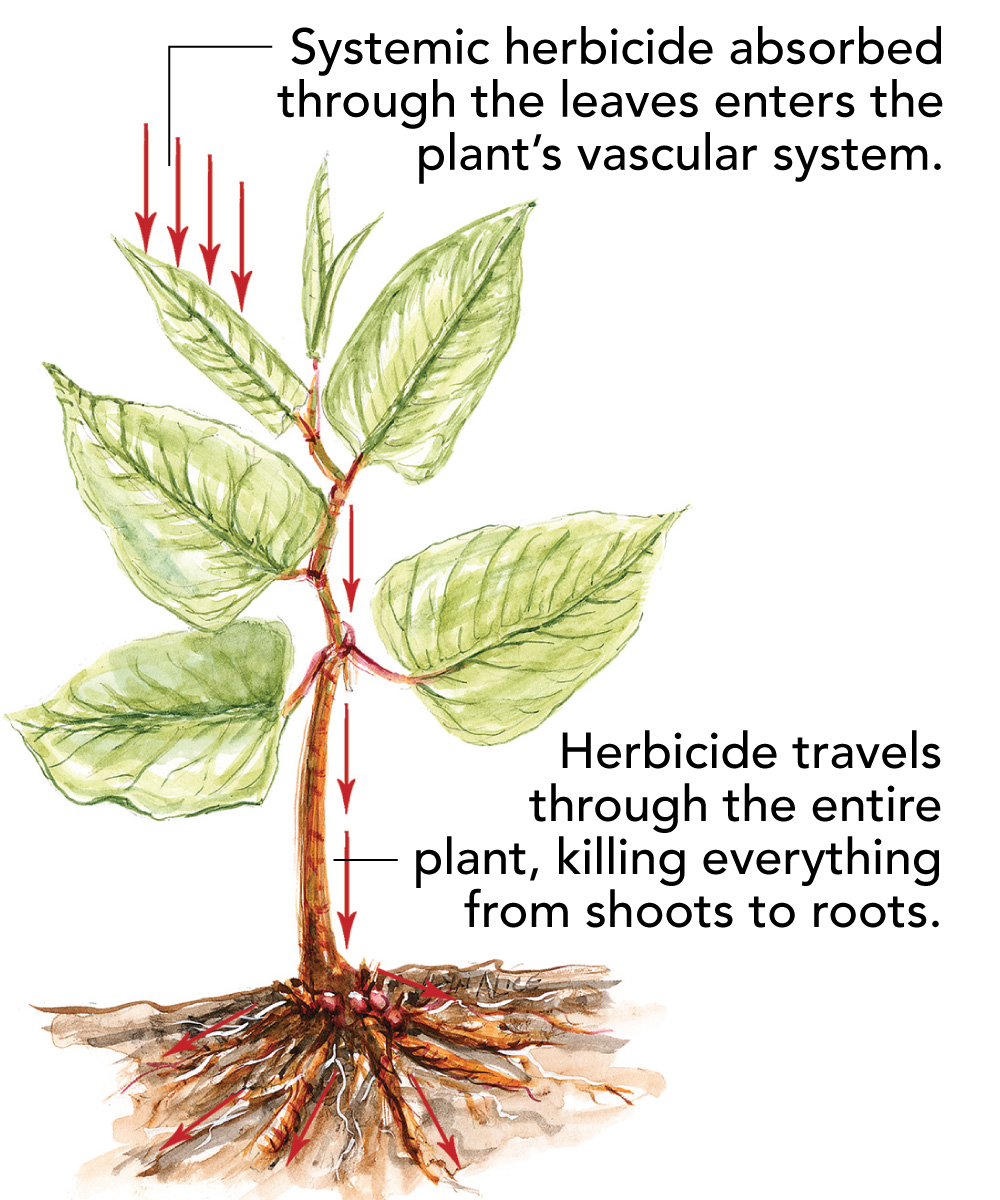

Removal option C: Apply herbicides

Systemic herbicides that can travel through the plant and reach the root are often the most effective way to control more-established populations. The timing of the application is often critical and varies from species to species, so do your research before applying any chemicals. The best information sources are the websites of government agencies, universities, and other research institutions.

Once you choose a product, carefully read the product label to learn about the proper timing for application, the correct procedure for mixing chemicals, and what equipment you will need to safely handle and apply the product. Meticulously following label instructions will ensure that you use the chemicals efficiently, reducing the risk of personal and environmental exposure.

4. Pull, dig, or cut invasive shrubs and trees

Many woody invasive plants, such as Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) and burning bush (Euonymus alata), have seeds that are spread by birds over long distances. This makes them more of a problem in natural and unmanaged areas than in a typical garden. If you have some of these plants in your landscape, the best practice is to remove them and replace them with noninvasive plants.

Removal option A: Pull the plant, roots and all

Plant extractors are some of the best tools for removing smaller-diameter woody plants. The Uprooter, Pullerbear, Weed Wrench, and Extractigator are comparable products, and all are very effective. These tools are operated by pulling on a long handle, which activates a clamp at the base of the woody plant and provides leverage to pry the plant out by the roots.

A mattock can also be an effective tool for removing larger plants. It has a wide, flat blade that slices through thicker roots that can be hard to cut with a shovel. It can also be used like a pickaxe to lever a plant out of the ground. This tool is especially useful for larger shrubs.

Removal option B: Cut down the top, and treat the stump

If manual removal of woody plants is not an option, herbicides can also be utilized. The cut-and-spray method is typically best; it reduces the amount of chemical used and the risk of spray drifting to nontarget plants. With this method, you cut all the woody stems down to a few inches tall, then immediately spray or paint the cut stems with an appropriate herbicide. Note that rates can vary for this type of application, so consult the product label. The best timing for this method tends to be fall, when the plants are starting to go dormant.

Tools worth trying

Having the right equipment can save time and energy. Here are a few tools you may want to add to your plant-removal arsenal.

Hori hori

This is an all-around great garden tool, but its best use is for removing smaller plant material. Most of these knives have a long tapered blade with one serrated edge.

Price: $22 to $49

Plant extractor

A plant extractor is worth the investment when a lot of woody plants need to be removed. For large jobs, it is more efficient than using a shovel.

Price: $125 to $249

Backpack sprayer

This tool carries more material than a handheld sprayer and is easier to use for extended periods of time. For smaller jobs, a handheld sprayer should be fine.

Price: $22 to $90

Mattock

This tool is useful for removing woody plants larger than what a plant extractor can handle. The wide, flat blade slices through thicker roots easier than a shovel and can be used to pry root balls out of the ground.

Price: $35 to $50

Erin McCormick is a horticulturist and member of the plant health team at Mt. Cuba Center in Hockessin, Delaware.

Illustrations: Lyn Alice Hamilton

Comments

It is important to start at the edges of any invasives patch and work toward the middle. They spread from the edges so stopping or slowing them there is vital. Also, efforts often must be frequent and on-going. Think too about what you can plant to compete once your diminished the invasive.

All useful information. I'm reminded that one well-known mail-order nursery was selling a supposedly sterile variety of purple loosestrife for some years before admitting that there was....a problem. With respect to tools, I love, love, love my mattock. It's great for getting small stumps out after cutting back all the branches (I'm looking at you, bush honeysuckle) and also for the first pass at prepping soil that hasn't been touched in 30+ years.

In the south the long growing season makes invasives a year around project. The common problem plants are mainly landscape plants from 50-100 years ago - English ivy, privet, eleagnus, bush honeysuckle, mondo/monkey grass, and wisteria. The unfortunate thing is that most homeowners don't know the problem, and landscapers plant them because they are cheap and hardy. We have hundreds of acres of urban park land that is clogged with these plants competing with and dominating the native wildflowers and shrubs.

The one positive note is the local zoo - Zoo Atlanta - has found giraffes love to eat cut privet plants, so we have teams of people cutting privet for pickup; and delivery to the zoo.

A very useful article, and not only for gardeners! I am studying ecology and am currently writing an essay on endangered and invasive plant and animal species. I also found a lot of interesting facts at https://eduzaurus.com/free-essay-samples/invasive-species/ and it turns out that invasive species can even affect a country's economy. I thought that this could affect the flora and fauna, but not the economy. But, if you think about it, you can understand that if a country earns money on agriculture (and not only), then invasive species will greatly affect economic indicators ...

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in